I haven’t managed to read until today “

The Wisdom of the Crowds”, James Surowiecki’s well mediatized book, though it’s almost impossible to read an article or book on collaboration without meeting at least a small reference to it, if not a quote from it. Through the quotes met on the web I arrived to grasp a little from Surowiecki’s philosophy, and even if I it’s not the same as the read itself, I decided to write this post before reading the book, attempting to see how much my ideas changed after reading it.

I have the feeling that many have misunderstood maybe what knowledge and wisdom is about, how things are harnessed and evolve in life. Many bloggers, reputed writers and philosophers, believe that the crowds, sometimes referred as the masses or the mob, can’t be wise but rather stupid, thus appeared terms like stupidity of the masses, madness of the masses, etc. They are not so far away from the truth, especially when they are referring to the uneducated masses or to the panic-like effects, however the reality is that even a simple person who worked the land all his life or any did any other type of work and had no time for school could have more wisdom than a phony intellectual who spent all his life on the banks of schools without achieving a grain of wisdom or even knowledge.

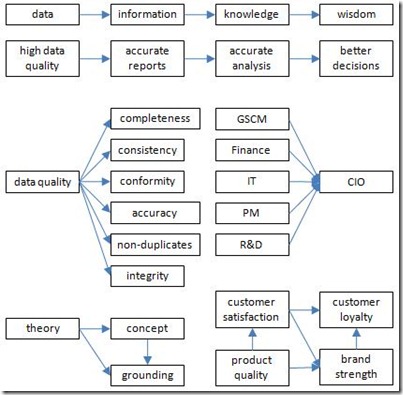

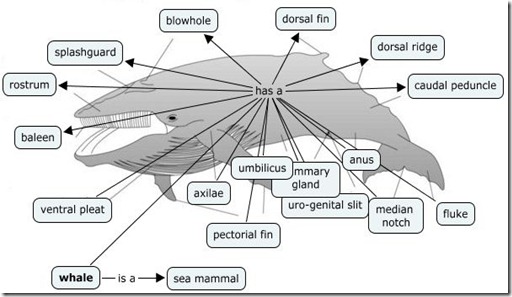

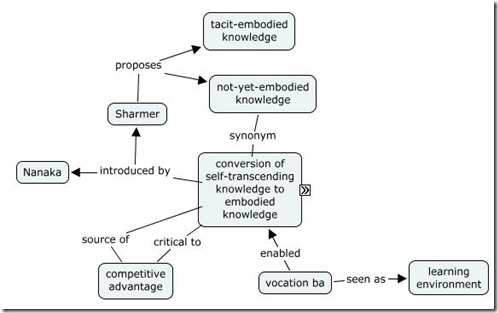

Again, with the risk of repeating myself, and as many have stressed, data is not information, information is not knowledge, and knowledge is not wisdom, the scale in this order implying a refinement and evolution of the thought process. Wisdom is a Holy Grail, and this not only in respect to spiritual life, but also to daily professional life, as it implies going above the knowledge existing in a certain field, either managerial, engineering, a simple job that pays the rent or any other activity. A simple person could hold his own grain of wisdom valid in his world, and with the eyes of an open mind and some chunk of knowledge from other domains, he might see the patterns a more educated person can’t grasp. For sure such a statement can’t be digested by researchers, especially when it’s almost impossible to express and measure wisdom, being more like a

Morgan le Fay. It seems that is more important to touch the rays of wisdom, however it’s difficult to delimit where ends knowledge and begins wisdom, plus the various facets of the two, and from here the almighty confusion.

Even if it’s difficult to believe that wisdom could be found at the fingertips of everybody, in definitive each person brings a different range of experiences, data, information and knowledge, different perspective of the same story, different cultural, social, geographical and cognitive aspects, in other words diversity of a wide range and richness. So on one side we are having the wisdom of the individual, even if it doesn’t fit the academic benchmarking for wisdom, but there is still some wisdom in there, and we have a network of people between each exists different grades of relationship (blood relation, friends, co-workers, neighbors, readers of the same material, etc.) with about 6 or less degrees of connectivity.

An old English proverb says that "two’s a company, three’s a crowd", and above its relevant meaning, it’s actually more important its value as output of masses’ wisdom. Sayings, stories, verses, songs and other type of cultural manifestation of the crowds, are examples of wisdom, condensed wisdom I might say. Somebody was saying that all the great ideas of mankind were thought with many ages before, nothing more truly, and we are just rediscovering them now through the advances of modern techniques and thought.

People might be illiterates but could be masters in manual work or in any field that doesn’t involve writing, people might be shy but find incredible creative force when they are talking about or expressing their passions, they could come with unexpected solutions to complex problems when the problems are broken down to their language. Sometimes only by having a real partner of discussion or having somebody to address to, a person arrives to discover new perspectives in the process of externalizing knowledge, come with a new idea or find the solution to a problem. As Mark Zuckerberg remarks, "people have really gotten comfortable not only sharing more information and different kinds, but more openly and with more people - and that social norm is just something that has evolved over time". And very important, people are willing to give their knowledge free if the right context is met, but how do we achieve that?

Coming back to the before mentioned proverb, it gives a minimal definition for what it means a company, with direct and figurative meaning, an association of two people, respectively a crowd, as an association of at least three people. Witty definition in common sense language, much less than the definitions given by the academic literature, isn’t it? It is necessary to say that here the meaning of association is quite rich, implying any type of association made between people who come in contact in a form or another – organizations, ways of transportation, in queue lines, in chat rooms, forums or within the boundaries of a social network, in fact any place in which some type of communication occurs.

Communication is the backbone on which our society is based, and there are so many aspects, but what is important to retain, is the sharing of ideas which occurs between two or more people, the mode in which the communicated data, information or knowledge shape us. There is a micro scale, in which the communication happens between any two people of a group, and a macro scale, in which the communication is regarded as a whole, though the interactions between all the members of a group. In both cases is important how the input is transformed, loosing or gaining content, what each person retains or contributes.

Researching the exchange of information occurred at multiple levels in our society is almost impossible, we only observe its effects, how markets change, how fast we receive important or irrelevant information, how meaning is changed voluntarily or involuntarily, altruistically or looking for profit. I’m mentioning this, because without understanding the whole process of communication and all its aspects we can’t use adequately the communication channels and harness the skills of people.

We could say that we are having the potentiality of crowds’ wisdom, but it depends how we harness it. Harvesting doesn’t resume in the ultimate action of taking the results of nature’s work, you have to invest some time in cultivating the seeds, take care of the plants, providing water and the needed care, the right temperature and fertilizer, consider the appropriate time for performing each action in the process. In addition you have to come also with some additional knowledge about the plants themselves, but also about the context, which is the best soil, what it takes to be in agriculture, to build an infrastructure for optimal work, etc. Who says that the same doesn’t apply to individuals and groups too?!

Individuals and groups need to be brought to the required level of education and knowledge in order to rise to the level of the demands. Wisdom involves some degree of knowledge and implicitly of information, the volume depending on the nature of the task at hand. Same you educate a kid upbringing him to a certain level of autonomy by repetitive task increasing in difficulty, upon its degree of understanding and pace, the same should apply to a group too, based on its intrinsic qualities and requirements. In the past years have been attempted to use the masses in order to solve several types of tasks, some with positive, but also many with negative results.

If the masses can’t solve a certain type or types of problems, this doesn’t mean that they are dumb and posses no wisdom. An example of such a “failure” is the attempt to predict the trends of the various types of markets by using the masses, though it’s hard to think that such experiments could come with positive results as long there are too many interests and people who want to make profit by influencing the masses. This aspect stresses especially the need for independence, which adds to autonomy and diversity, other two characteristics that needs to be met by the crowds.

It’s also important to address a problem to the right community. I doubt, for example, that a complex problem of physics could be solved by addressing it to a group of sportives, excepting the cases when you talk about sportive physicists. Mentioning people who have knowledge coming from two or more domains, they are quite important, but not necessarily the most important. Depending on the problem at hand, the group should have a set of given properties that would allow it to approach and solve a problem.

There are many more aspects that need to be considered in relation to the crowds, hopefully I will manage to develop the ideas in a series of other posts.

![must_buy_twitter_shopping_list[1] must_buy_twitter_shopping_list[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgMTd1NyVp5UxkR1s3MQrjGP0z77MwxLHK-BlMIpnUOgv_NxXva0wnJ-yoiPSCMS9KBF7mOBWJuJFP4GHBXzlPpfQZE1PDFNMH-T498OI0Q90vFDOel-YlcfvJywI44acFkj8lbNWT0lRQ/?imgmax=800)