Knowledge could be broken down to concepts and the associations between them, words functioning as links between concepts. A concept could be seen as a unit or chunk of meaning, for example “mother”, “father”, “child”, “home” are a few of the concepts we incorporate in our conceptual vocabulary, the collection of concepts we hold in our mental world. The previous four mentioned examples are just words, though words are just labels, transporters of meaning, and they don’t equate to concepts. A word (written or spoken) same as an image, a symbol or sound are just a representation/externalization of a concept outside of the mental world, we could regarded them simple as labels. Sure, they are strong correlated, and concepts could exist without labels, same as labels could exist without the articulation of a concept in the mental world. In a simpler formulation we could say that:

Label + Meaning = Concept

Meaning and labels are concepts too, fact that makes the definition kind of redundant, but that’s less important as long the overall meaning is understood. In addition the concept of meaning is quite complex, meaning being considered as existing within a given context, a context that carries its own meaning and it’s a concept in itself. More redundancy, isn’t it?

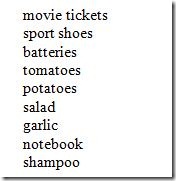

We could in theory put on a paper all the concepts we know, to be more focused, all the concepts we know related to other concept functioning as topic. Such constructs are similar to the ones of tag clouds, user-generated tags used to describe the content of a web page. Another type of such collection of concepts is the shopping list or any other types of lists.

![must_buy_twitter_shopping_list[1] must_buy_twitter_shopping_list[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgMTd1NyVp5UxkR1s3MQrjGP0z77MwxLHK-BlMIpnUOgv_NxXva0wnJ-yoiPSCMS9KBF7mOBWJuJFP4GHBXzlPpfQZE1PDFNMH-T498OI0Q90vFDOel-YlcfvJywI44acFkj8lbNWT0lRQ/?imgmax=800) |  |

| Example of tag cloud | Example of shopping list |

Each of the words from the above tag cloud, respectively shopping list, are labels of the concepts they represent. In contrast to the shopping list, the size of the labels used in the tag cloud is proportional with their occurrence, but that’s less important for now. The fact is that both are representing a collection of concepts. More complex collections could be based on concepts derived from scientific works, book indexes are another such of example.

In the above shop list, “movie tickets” is a multipart label for a “single” concept, though it’s composed of the labels of two different concepts – “movie” and “ticket”. In this way concepts/labels could be formed by the aggregation of meaning for concepts, respectively concatenation of labels for labels. In theory we could put together as many of concepts or labels as we wish, though there are some limits imposed by linguistics. In daily life aggregations/concatenations of 2-3 concepts/labels are pretty usual: “knowledge mapping” (= “knowledge” + “mapping”), “knowledge management”, “business intelligence”, “collective intelligence”, “harnessing collective intelligence”, etc. There are also examples of labels encompassing already a concatenation of other labels, words formed with prefixes (e.g.: “un” + ”believable” = ”unbelievable”), affixes (“engineer” + ”ing” = ”engineering”) or hybrid/compound words (e.g. “auto” + ”mobile” = “automobile”) are the simplest examples we used on a daily basis, some of the languages being more abundant than the others in such compounds (e.g. German language is quite rich in such hybrid words).

The linguistics and semantic meaning of words offer us a deeper overview on the formation of words and meaning, though we don’t have to go that far. I will just limit myself to mention that a morpheme is the smallest compound of a word, composed at its turn of multiple phonemes, the smallest linguistically distinctive units of sound, and graphemes, the smallest units of written language. In addition words or labels does not necessarily have to respect the rules of language morphology as a whole, one of such compounds that entered in my vocabulary many years ago, comes from the Disney’s musical film Mary Poppins, and those who the movie, probably already intuit what I’m talking about: Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious is formed, according to Wikipedia, from the following morphemes: super- "above", cali- "beauty", fragilistic- "delicate", expiali- "to atone", and docious- "educable", and the sum of these parts signifying roughly "atoning for educability through delicate beauty".

Given the richness of languages in what concerns the morphology, syntax and declension, how do we choose the labels? Also this is a complex topic and my knowledge stops somewhere. I prefer to use the infinitive form for verbs, nominative and singular form for substantives, sometimes called the dictionary forms, and include the prepositions when they change the meaning (English language is full of such constructs). It’s not always so easy to do that, but I try to stick to it whenever is possible. In what concerns the labels formed of multiple other labels I prefer to choose the smallest unit of meaning that defines a concept “uniquely”.

Classes of Meaning

A class of meaning equivalence, shortly class of meaning, comprises all the labels that share the same meaning [1]. Such a class comprises all the synonyms, acronyms and forms of construction of natural language used to label a concept. For example, depending on context, any of the following labels could be considered as belonging to the same class of meaning: abode, apartment, flat, home, mansion or residence. Many of us use acronyms in daily life, with formal or informal character: EOD (End of Day), ASAP (As Soon As Possible), US (United States, Uncle Sam, Upstream, Ultrasound), KM (Knowledge Map, Knowledge Management, Knowledge Mapping, kilometre), etc.

The syntagm “forms of construction of natural language” refers primarily to the various elements of orthography hyphenation, capitalization, word breaks, emphasis and punctuation, which introduce some variance in the labelling of concepts. On whether we write “knowledge based” or “knowledge-based”, “center” or “centre”, “Knowledge Management” or “knowledge management”, “class of meaning” or “meaning class”, the various labels refer to the same concept. Normally in a Map would be enough to include only one member of a class of meaning, unless is intended to highlight the synonymy or any other similar association type.

No comments:

Post a Comment